Orienteering skills

This is an overview of basic orienteering skills and how to

teach them as a parent, teacher or youth group leader. It is

also useful as a quick primer for a newcomer wanting to learn

some basic skills. More details can be found in the books for

teaching young orienteers listed in the resources section. Orienteering vendors have

vast collections of literature, materials and equipment for teaching

and learning orienteering.

Of course, the best way to learn or teach orienteering is

to do it, so by all means get out onto a map! An orienteering

event organized by a local orienteering club can often be the

best way to get a good suitable course and map, and yield a rewarding

experience.

I'll start with skills for very young children. Older children

and adults may want to start with adult courses, but be sure

the basic skills are taught: orienting the map, understanding

the map symbols, and so forth.

Getting used to the forest

Younger orienteers may want to do activities to get used to

being in the forest, to help their self confidence and sense

of security. String orienteering courses are helpful for this,

since they eliminate the risk of getting lost. So are other activiies

and games done in the woods.

What is a map?

One way to think of a map is as an aerial view. But for younger

children, the concept of a map as a drawing of the forest may

be more easily understood. An intuitive understanding of a map

is a good base from which to build on later with more formal

concepts.

Frequent exposure to maps helps build a sense of familiarity.

Foster this by asking simple questions about the map. If the

map is colored, quiz the child on what the colors mean -- yellow

for clearing, blue for water and so on. Talk about places being

far apart (or close together) since they are far apart (or close)

on the map. It may be good advice to not get too complex too

soon; the child may not yet be ready. Maps are a wondefully intuitive

and yet sophisticated concept that children will grasp when they

are ready.

Simple exercises include having children draw a map of a small

area. This can be as simple as making a drawing of a room or

a field, or as fromal as measuring a room or field and the objects

within and drawing them all to scale on graph paper. Choose the

level of sophistiction suitable for the child.

If you discuss contours or topography at this stage, it may

be good to start simple. Simple concepts to start with include

hilltops (shown by closed contours, and the difference between

steep areas (where contours are close together) and flat areas

(where there are few or no contours).

Reading a map

Lead the children out on a map walk reading the map. Point

out features as you go along. Ask the children to anticipate

what features they will be seeing next by reading the map.

Orienting a map is an important skill. Turn the map until

what is in front of you in the terrain is in front of you on

the map. If you are facing east, then the east side of the map

should be away from you. Don't worry if the lettering on the

map is sideways or upside-down. Practice keeping the map oriented

while on a map walk.

Thumbing is also a useful technique. Fold the map into a small,

easily held piece and hold your thumb on the map near where you

are. Keeping your thumb near where you are as you go along makes

it easier to refer back to the map when you take your eyes off

it. It also reduces the chances of your eyes “skipping”

to another part of the map, say, to another trail junction. This

is an easy error to make.

An example of a map reading exercise is to have the children

do a String orienteering course. Mark the route on the map for

them but don't show where the controls (checkpoints) are. As

the children come to each control, have them mark where they

are on the map. This will teach them to read the map and figure

out where they are.

Learning to navigate

Navigation is the quintessential skill of orienteering, and

it will take time to master. Be sure to teach (or learn) it progressively

in small steps, allowing for success at each stage. Children

may also still want to do the String course as well as they advance

to adult navigation, which is good, since String courses often

serve a social function as well, and help reinforce a sense of

success.

Navigating along linear features

Once children can find their location on a map, the next step

is to start finding their own way on an unmarked route...in other

words, on a standard orienteering course. At first, do the navigation

together.

The first type of standard orienteering course for a child

to do is one on linear features, such as trails, with only one

decision to be made on each leg. (See Learn the language). For instance, each control

might be on a trail junction, but there should not be any trail

junctions between controls. At each trail junction the child

need only decide which way to go, This is easier than a typical

White course, which is the easiest standard course usually available.

You may need to improvise:

If you set the course yourself, use a small, well bounded

area. If you want to use a normal White course, try to pick an

event at an area that tends to have easier White courses, such

as a small park. Or, if the course is hard, have the child do

the navigation for some of the easier legs and do the harder

legs together.

Don't worry about choosing the best route or the fastest way,

just successful navigation. Route choice tends to improve with

experience.

After children master simple linear navigation, they are ready

for a more typical White course, where they will make multiple

decisions on each leg. Follow them along at first, letting them

navigate but keeping them from making big mistakes. Later, let

them do the course alone.

At some point, teach a second technique for orienting the

map: using a compass. Hold the compass on the map. Ignore all

settings, dials and gadgets. Turn the map (not the compass) until

the compass needle is parallel to the north lines on the map,

with the red end of the needle toward the north end of the map.

(The compass needle always points to north (magnetic north, to

be specific), so turning the compass will leave the compass needle

always pointing the same way.) Now the map will be oriented with

the terrain, just like when you oriented it before.

Practice map reading while on White courses. While going along,

have the child read what other features should be alongside the

trail, and verify that these are there as you pass them. Also,

practice relating disctances on the map to distances on the ground.

For instance, how far will the next feature be?

Off trails

The next more difficult course is Yellow. The Yellow course

generally goes along trails and other linear features, but often

has controls on features just off the trail.

Now it becomes important to plan a method of finding a control,

not just picking which trail to take. Often this involves an

“attack point,” which is a feature, such as a bend

in the trail, or a pond by the trail, or a hilltop, or such,

at which you will head offf the trail to find the control. Ther

times it may simply involve knowing when to look for a small

hill or cliff near the trail. In any case, it is important to

plan ahead.

Route choice starts to become important. At this point emphasize

routes that provide the most sure way to find a control, rather

than the fastest or shortest way. Consider factors such as whether

there is a feature (“catching feature”) to let you

know if you have missed what you are looking for. Is there a

good atack point on this route? Is the navigation easy or hard?

Are there lots of chances for wrong turns?

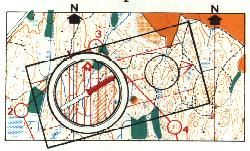

Compass bearings could now be taught:

Place the edge of the compass

on the map so that it goes from where you are to where you want

to go. (So, the edge of the compass forms a line connecting where

you are on the map and where you want to go.) In the diagram

above, a compass bearing is being taken from a trail bend to

control point 3. (A trail is shown by a dashed black line; a

red mark has been made on the diagram to point out the trail

bend.) Make sure that the direction of travel arrow at the top

of the compass is pointing in the direction you want to go, and

not in the reverse direction.

Place the edge of the compass

on the map so that it goes from where you are to where you want

to go. (So, the edge of the compass forms a line connecting where

you are on the map and where you want to go.) In the diagram

above, a compass bearing is being taken from a trail bend to

control point 3. (A trail is shown by a dashed black line; a

red mark has been made on the diagram to point out the trail

bend.) Make sure that the direction of travel arrow at the top

of the compass is pointing in the direction you want to go, and

not in the reverse direction.

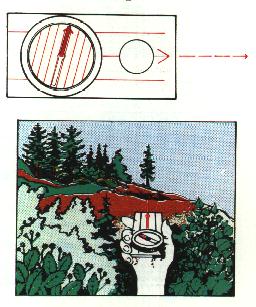

Holding the compass in place on

the map, and ignoring the needle for the moment, turn the dial

so that the lines in the housing line up with the north lines

(meridians) on the map. Make sure that the N on the dial is towards

the north (and not south) end of the map. (This is subtle in

the above diagrams; look to be sure you see it.)

Holding the compass in place on

the map, and ignoring the needle for the moment, turn the dial

so that the lines in the housing line up with the north lines

(meridians) on the map. Make sure that the N on the dial is towards

the north (and not south) end of the map. (This is subtle in

the above diagrams; look to be sure you see it.)

Leaving that setting alone, turn

yourself and the compass and map until the red end of the needle

points to the N on the dial. (Remember, the needle doesn't turn

(it always points north). You and the compass and map turn around

it. This takes a bit to get used to.) The direction of travel

arrow on the compass now points in the direction you want to

go.

Leaving that setting alone, turn

yourself and the compass and map until the red end of the needle

points to the N on the dial. (Remember, the needle doesn't turn

(it always points north). You and the compass and map turn around

it. This takes a bit to get used to.) The direction of travel

arrow on the compass now points in the direction you want to

go.

Illustrated instructions are often included with orienteering

compasses. Remember that the most important use of a compass

is still to orient the map. And remember, reading the map is

still important too!

At this stage, an orienteer is probably ready to make a very

simple map of a small area, such as a schoolyard. This is excellent

training for both map and compass skills, and will reinforce

almost everything taught to this point. An orienteering training

camp might also be useful and fun. More advanced skills can be

found in several of the books listed in the Resource section.

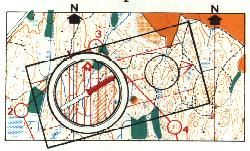

Place the edge of the compass

on the map so that it goes from where you are to where you want

to go. (So, the edge of the compass forms a line connecting where

you are on the map and where you want to go.) In the diagram

above, a compass bearing is being taken from a trail bend to

control point 3. (A trail is shown by a dashed black line; a

red mark has been made on the diagram to point out the trail

bend.) Make sure that the direction of travel arrow at the top

of the compass is pointing in the direction you want to go, and

not in the reverse direction.

Place the edge of the compass

on the map so that it goes from where you are to where you want

to go. (So, the edge of the compass forms a line connecting where

you are on the map and where you want to go.) In the diagram

above, a compass bearing is being taken from a trail bend to

control point 3. (A trail is shown by a dashed black line; a

red mark has been made on the diagram to point out the trail

bend.) Make sure that the direction of travel arrow at the top

of the compass is pointing in the direction you want to go, and

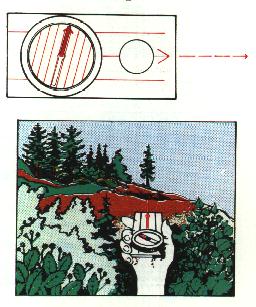

not in the reverse direction. Holding the compass in place on

the map, and ignoring the needle for the moment, turn the dial

so that the lines in the housing line up with the north lines

(meridians) on the map. Make sure that the N on the dial is towards

the north (and not south) end of the map. (This is subtle in

the above diagrams; look to be sure you see it.)

Holding the compass in place on

the map, and ignoring the needle for the moment, turn the dial

so that the lines in the housing line up with the north lines

(meridians) on the map. Make sure that the N on the dial is towards

the north (and not south) end of the map. (This is subtle in

the above diagrams; look to be sure you see it.) Leaving that setting alone, turn

yourself and the compass and map until the red end of the needle

points to the N on the dial. (Remember, the needle doesn't turn

(it always points north). You and the compass and map turn around

it. This takes a bit to get used to.) The direction of travel

arrow on the compass now points in the direction you want to

go.

Leaving that setting alone, turn

yourself and the compass and map until the red end of the needle

points to the N on the dial. (Remember, the needle doesn't turn

(it always points north). You and the compass and map turn around

it. This takes a bit to get used to.) The direction of travel

arrow on the compass now points in the direction you want to

go.